From Scattered Landscape to an Interconnected Ecosystem: How funding feminist and justice organizing can, do, and be better

New Shifts, Same Old Questions

If you’ve spent any time in a feminist space in the last decade or so, you’ve heard the question, “Where is the money for women’s rights?”

AWID and its partners and allies have been asking this question since the early 2000s. Results have shown that women’s rights organizations are grossly underfunded and many operate with under USD 20,000 a year with little access to flexible, general, multi-year support. Activists and funders have taken up this research in their advocacy to shift the balance of resourcing.

Despite some progress, after years of monitoring, researching, and advocating for more and better money, the current funding landscape is far from adequate to respond to the needs and demands of the movements to advance rights and justice. It follows what Michael Edwards, writer and activist in the field of philanthropy and social transformation, terms an “infrastructure,” comprised of discrete pillars of funding, categories of different actors and sectors, each with their own accountability mechanisms and decision-making structures and processes. With the exception of some public funds, women’s funds, and self-generated income, the majority of these pillars and their decision-making processes do not sit with the movements directly.

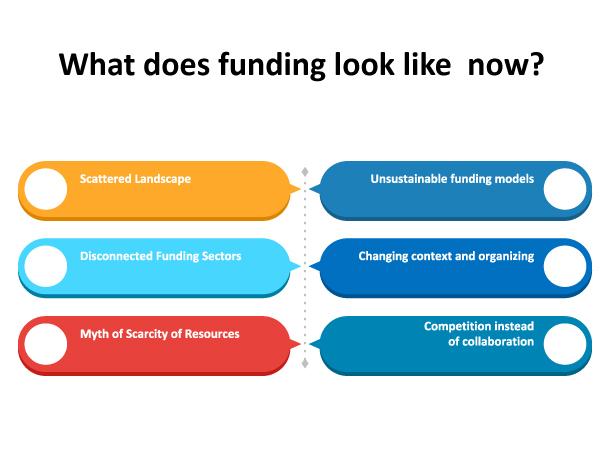

This scattered landscape creates unnecessary hoops and challenges for organizations and activists at different levels to secure, monitor, and advocate for funding.

It is time to take on a new path. We need to move away from thinking about funding in terms of an infrastructure with pillars and actors in watertight compartments and instead focus on interdependence, correlation, complementarity, and value add. We argue that a fruitful way of doing this is through a feminist resource ecosystem. This framework will be a shift from funding landscape to a funding ecosystem, where actors, sectors, mechanisms, sources interact in more connected, coherent, and complementary ways.

So how do we get there?

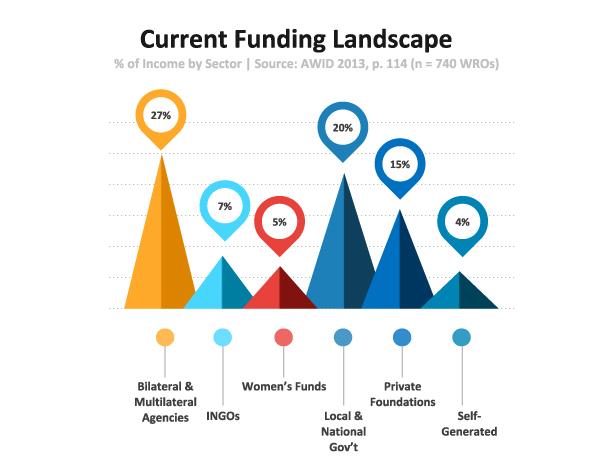

The current funding streams for women’s rights and feminist organizing can be described as falling under three pillars with a range of actors in each.

Institutional:

These are forms of funding resources that includes philanthropic, governmental, bilateral and multilateral support and stem from the public sector, private foundations, donor NGOs/INGOs. They are often large in amount and may be used to fund progressive causes and underfunded areas, at times, but are also fully guided by changing political priorities and/or personal priorities of the donor.

Commercial:

This includes funding that use the market to breed funding for social change. It include commercially generated resources like fees for services, pro-bono services or entrepreneurial endeavours, corporate support and investments, and a broader private sector engagement through Social Corporate Responsibility or direct business arms of corporations. It also includes private investors setting up and meeting their own social goals through for example cause-related marketing or when part of the surplus is dedicated to social causes.

Movements’ self-generated funding:

The autonomous funding pillar include self-generated resources through membership fees, crowdfunding, community support, bartering exchanges between groups, ‘giving circles’, cooperatives, pooled resources and the growing importance of diaspora funding. In an era of shrinking space for civil society and democratic actors in general and women’s rights in particular, autonomous funding is increasingly important. Key actors under this pillar are feminist activists and movements themselves.

In terms of the amount of money coming specifically to women’s rights and feminist organizations from within current landscape, here are some numbers presented in this graph from previous research by AWID:

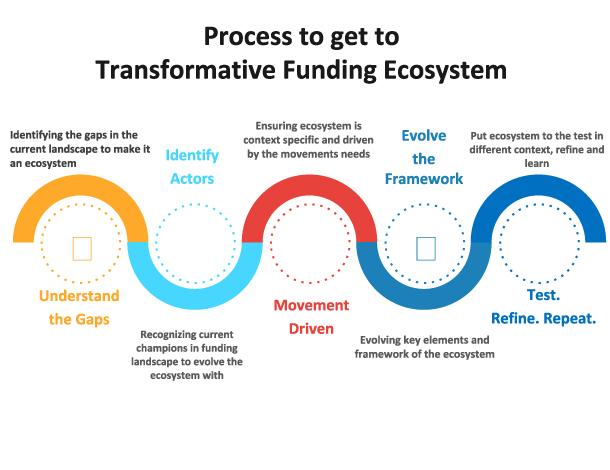

The ecosystems approach challenges us to think about funding social transformation in a radically different way. Instead of understanding funding as discrete and concrete structures with pillars and sectors, it draws first and foremost on movements’ needs and priorities and identifies funders as active agents in collaboratively supporting those priorities. Instead of a focus on scarcity, the possibilities of abundance, and diversity in the funding ecosystem are emphasized. Instead of fixed and siloed, social transformation is recognized as complex and interconnected, building on the idea that “the whole is or can be more than the sum of its parts.” And instead of looking upon donors and social change activists as disconnected and one depending on the other, it recognizes the relationship between the two and moments when one or the other is needed.

Let’s get more concrete. A funding ecosystem is made up of different, diverse, and not always complementary elements that, combined, can offer choices for different types of organizing to thrive instead of either having to shut down or adapt to what is available. In this approach, a discrete funder would no longer ask “What should my grant strategy be? What should I prioritize?” but rather, “What role can I play - based on my particular assets and constraints -- to complement and bolster the overall resourcing for movements?” This compels both an analysis of the current state of organizing and an honest conversation about how funders interact and strategize across different sites. In a healthy, movement-driven ecosystem, these questions should always be paired with, “Are we collectively supporting movements’ own priorities? What are we missing?“

In an ecosystem, funders are not just the grants they make. They are a particular point within a much larger system of interlocking resources. Within a single institution, sources of income, from endowments to governments to individual donors, also become sites of potential advocacy and social change. Funding is also placed in a larger context of overall flows of resources -- such as the USD 1,686 trillion for annual global military spending and the concentration of 50% of the world’s wealth by 1% of the population -- to undo the myth of scarcity and identify new ways we can think of accessing services and systems that could support more just societies.

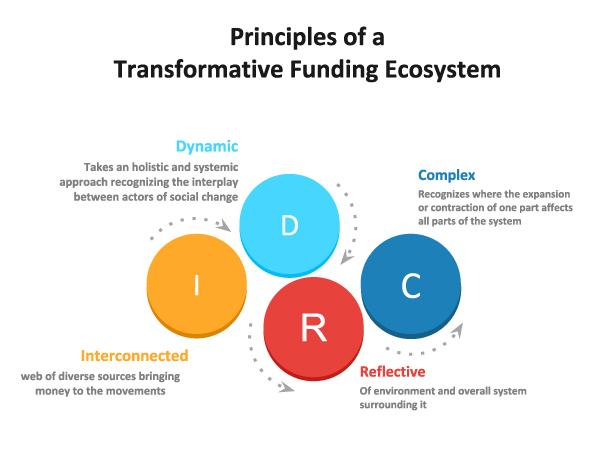

As compared to the current landscape approach, such an ecosystem would be driven by four principles: It would be: dynamic, complex, interconnected, and reflective.

For feminist, gender justice, and women’s rights movements, the ecosystem approach helps support and strengthen the funding security and, again, places the onus on funders to understand their own power and role within a larger field of resourcing. Importantly, the focus is redirected from donor- to movement-driven funding. In other words, away from how donors want, can, and should fund feminist organizing, to how activists themselves think resourcing should look like. The healthy balance we argue for is one where there is greater space made for a broader range of funding models, including those that are led by movement voices and movement-centered priorities. It also ensures that defenders, organizations, and groups are not stifled by sudden changes in priorities and directions of homogenous funding sources.

Moving from landscape to ecosystem does not mean that it will all be harmonious, peaceful, and free from domination. Imagine marshlands, jungle, desert -- at times not harmonious, not peaceful for some, and certainly not without dominations. Moving from a landscape to ecosystem paradigm is not a naive intellectual exercise but an experimental proposal that, at the core, attempts to challenge current funding situation for feminist and justice organizing and propose shifts and new questions for all the actors in the .. dare I say .. ecosystem … to sit with, play with, and address.

This essay is also available in audio format: